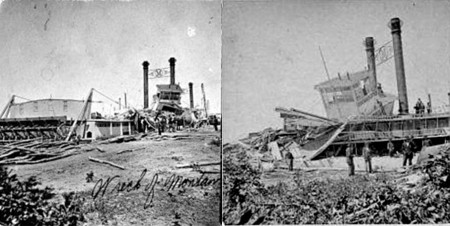

My Dakota Datebook today tells the tale of the Wreck of the Montana. In June, 1879, a tornado hit the boat landing at Bismarck, wreaking havoc on the steamboats moored there. Three were tied up; the Montana’s sister-ship Dakotah and the Col. Mcleod made it through with minor damage. The Montana, pictured below, didn’t fare so well.

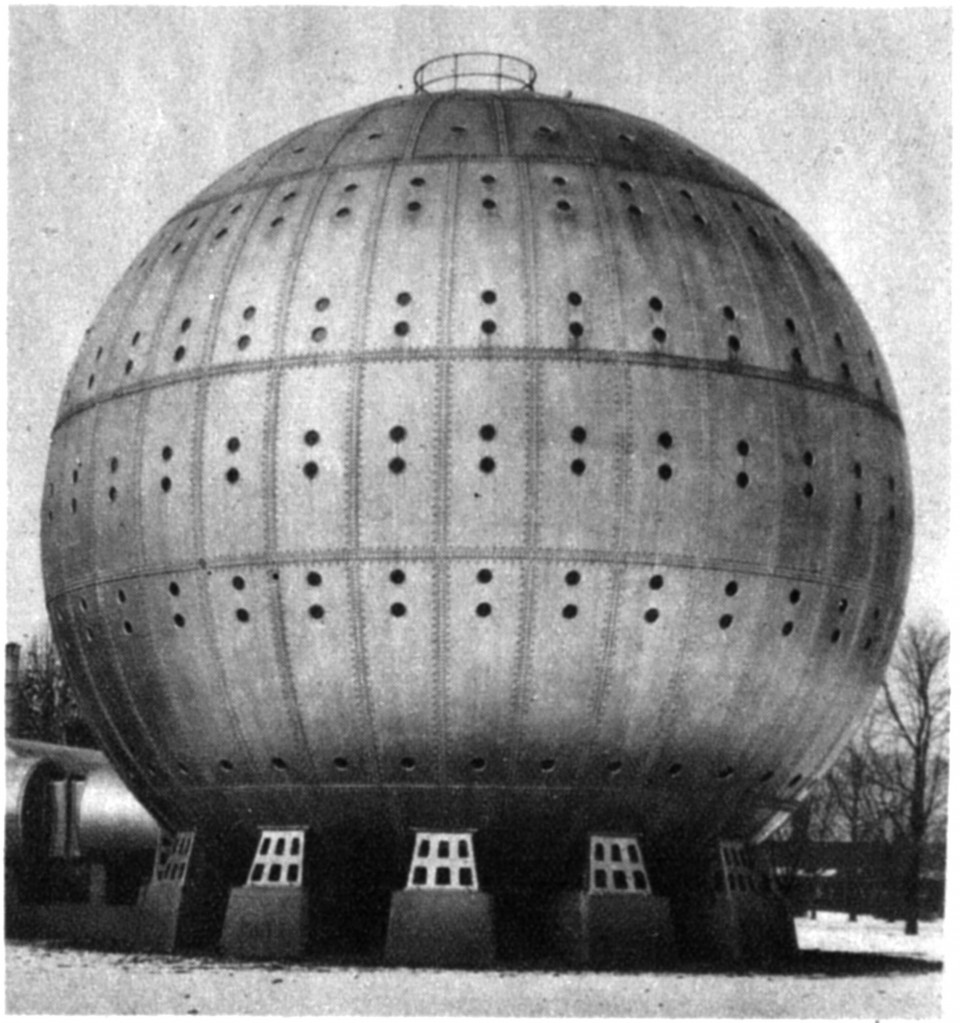

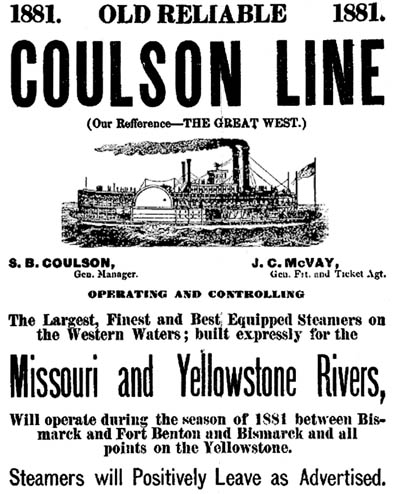

The Coulson Line had the largest, fastest, and finest fleet of steamboats on the Missouri River. In early 1879, the newly-launched Montana was their flagship of a half dozen large riverboats. She was 250 feet long, 48′-6” wide, and had a two-cylinder steam engine. Each cylinder was 18″ across and had a seven foot stroke — a massive engine to push around the largest stern paddle wheel ever made, eighteen feet in diameter and 36 feet long. The size of the Montana provided plenty of room for both passenger cabins and cargo holds, and even with 500 tons of weight on board only drew 3 feet of water.

In June of 1879, Captain Buesen had climbed to the top of the Montana to make sure the smokestacks were secure — unfortunately, they were about the only thing that survived when the tornado hit, along with the hull. The cabins were torn apart, the pilot house is tipped forward over the bow, mass destruction ensued. Only four members of the crew were on board when bad weather hit, and all survived with minor injuries. The Montana, however, had to be sent in for repairs.

After a season in the shop, the Montana was put back into service on the lower Missouri and possibly also on the Mississippi and Ohio for a time.

On June 22, 1884, however, the Montana made its last voyage. Loaded with freight, the steamboat hit either a submerged log or a bridge piling and sank near Bridgeton, Missouri. The captain at the time, Bill Massie, managed to limp the Montana onto a sandbar near shore where the boat finally sank to the bottom in only a few feet of water. The shallow wreck allowed for much of the cargo to be salvaged.

The Montana, however, rises from its grave from time to time. The wreck was never entirely salvaged; when the water level of the Missouri drops due to drought, like last fall, you can see the remains of the Montana’s hull in the muddy banks of the river. This has been a boon to researchers, who have little left to go on for these huge steamboats of the Missouri.

You can learn more about the Montana in the book The Steamboat Montana and the Opening of the West, which I sadly have not read yet but is now on my list.

It reads:

It reads: