Happy New Year, and maybe you haven’t heard, I’ve opened up a new small part of this website a couple months ago. Dakota Death Trip is a compilation of vintage news articles, photos, and other information, combined to give a picture of the harsh uniqueness that was North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Montana homesteading a hundred years ago. Start here for a more detailed explanation, or go to today’s story and work your way backwards to get the full effect.

Author: Derek Dahlsad

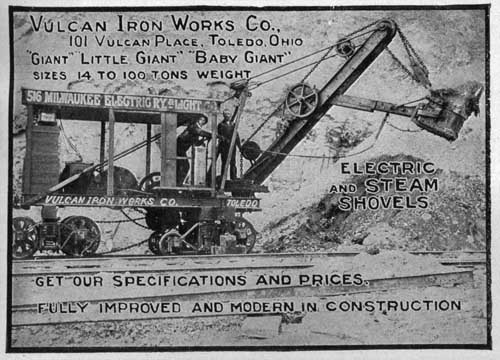

Electric and Steam Shovels, 1905

As technology changes, sometimes we get stuck on old terminology; we “dial” a phone, the first TV channel is “2”, and we flatten things with a “steamroller”. Most steamrollers today, of course, are gas or diesel powered, but they’re still ‘steam’ to us. Steam-power ran most construction machinery in the 19th century, but slowly faded out as modern power systems became reliable. I still call big loaders “steamshovels”, even though they haven’t been steam-powered in a hundred years – but, unlike many other forms of technology, steamshovels took a leap to electricity early on. In fact, a lot of heavy machinery was (and still is) electric, because distance and freedom of movement wasn’t as big a deal, and effectively ‘outsourcing’ power generation reduced weight and complexity. Vulcan Iron Works produced steam shovels since the 1890s, and in this 1905 ad they were showing their steps into The Technology of Tomorrow: Electric Shovels. Vulcan was bought by Bucyrus five years later, and they’re still in making mining equipment today, although under the Caterpillar name. As far as terminology goes, “Electric Shovels” are now known more generically as Power Shovels.

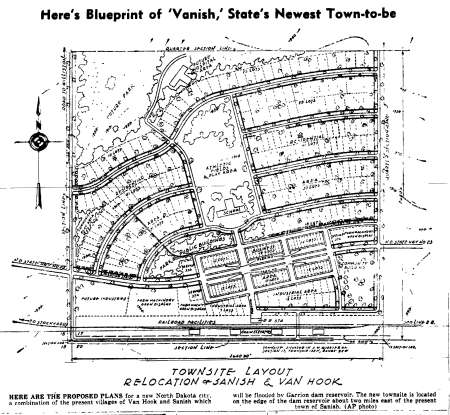

Vanish, North Dakota, 1950s

In the early 1950s the Garrison Dam was well under construction, and the government was working on accommodating several communities that were about to be soaked by the newly-formed Lake Sakakawea. Two villages, Van Hook and Sanish, were only a few miles apart with a little ridge of high land between them, so a new town was platted out in the middle. The media wittily called the new town Vanish, a play on Sanish’s name and its unavoidable fate, but there’s no “Vanish, ND” on the maps today. When you lay the map below over nearby towns to figure out which one this is, you realize that the government was far less witty than the newspapers. The powers-that-be named the new town…New Town.

WWI Poem, 1948

“Just a thought

And just to think –

A slap of ink, embroiled the world

in War! A fleet of ships through “U” boats slink –

A Kaiser is no more.”

I tried to find a source for this little, not-quite-rhyming poem, that was near the end of my great-grandfather’s WWI memoir, but I came up empty. Turns out that, besides surviving mustard gas and coming back to North Dakota to make a family, he also had a little bit of poet in him. I had a short day at work, so I used my free time on Veteran’s Day to transcribe his entire memoir, which is linked just above.

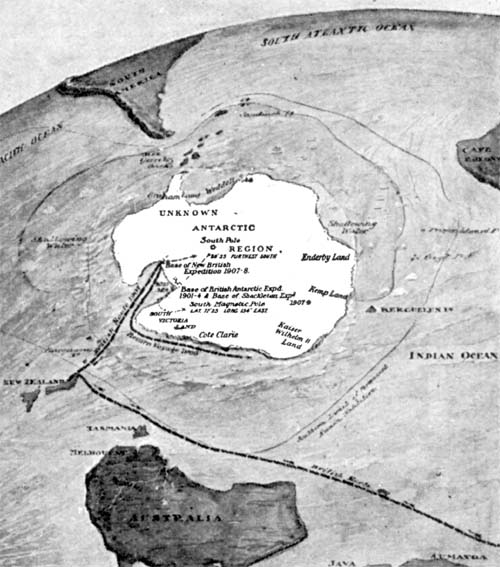

Antarctica, 1890s.

It is usually left off of world maps, but in this one Antarctica is the guest of honor. Most flat map projections, even if they do include Antarctica portray it as a wide band of white, with little visualization of how it actually appears. Above is a map viewing the spherical Earth from a southerly position, providing the least distortion to Antarctica, but giving a very different view of where South America, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia lie in relation. The map’s purpose is to show various expeditions to locate the South Pole; the map was reduced such that the labels are almost unreadable even in the original. From the multivolume The Book of History, 1890s.

Rural School, 1930s.

A rural brick school, done in the style of numerous schools that were built during the 1920s and 1930s. Few rural school-buildings are still operating as schools today; if they are, the original building has been added on to numerous times over the past seventy years to accommodate growth or consolidation. Others have been torn down, sit in disrepair, or — the lucky ones — have been taken over by the historical society, an antique shop, or some other business and restored to usefulness.

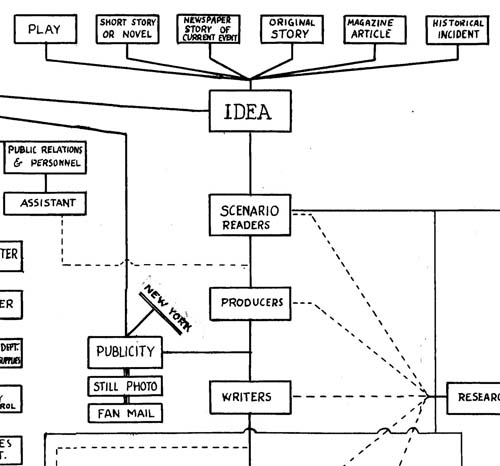

IDEA, 1940s

When producing a movie, everything stems back to this box: IDEA. In the 1940s, these were the sources of ideas: “Play,” “Short Story or Novel,” “Newspaper Story or Current Event,” “Original Story,” “Magazine Article,” or “Historical Incident.” Way off on the left, however, there’s one additional source that’s not shown above: “Vice President in Charge of Production.” If you want something unoriginal done that isn’t in print or in the history books, go talk to the VP, he’ll get it done. On another note: this particular flowchart is one of the few places the words “Restaurants,” “Mimeograph,” “Arsenal,” “Publicity,” and “Bits & Extras” fit together so well. From the 20th Century Fox flowcharts collection.

A Warm Stove, 1930s.

Warming by the stove, 1930s. From this series.

Camera for the Year 2000, 1968.

In the late 1960s, Zeiss-Ikon designer Fritz Costabel was trying to wrap his brain around the Camera Of The Future. In an early 1968 issue of Photoguide Magazine, he described a machine capable of sending photos home wirelessly, radar auto-focusing, and push-button automation. A few months later, the camera above showed up in Mechanix Illustrated: the Zeiss-Ikon “Utopica”. Looking a phaser sidearm off the Star Trek set, the camera was a multifunction machine: it could both instantly print photos like a Polaroid, but also make movies on 16mm film. The un-ergonomic shape and the focus on analog film were a bit short-sighted, but he was just about right on. Cameras today are automatic, double-duty as movie cameras, and can instantly produce a photo and allow it to be sent all over the world – and it certainly would have blown his mind to know that all of that photographic futurism is today considered an add-on to a portable telephone.

German POWs in Minnesota, 1940s

As World War II progressed, captured German soldiers were increasing in numbers, and the U.S. needed to do something with them. Numerous POWs were scattered throughout the country and used as labor. Algona, Iowa was the main POW camp in the United States, and several Germans were sent to Algona Branch Camp Number 1 — located in Clay County, Minnesota, just across the river from Fargo. Farm labor was scarce due to the number of men recruited for the military, so POWs helped in the cultivation and harvesting of the crops. This was not a forced labor program; the German soldiers were paid for their work. The above photo was taken at on the Paul Horn farm; Horn was chosen to take POWs because of his position on Clay County’s Farm Labor Advisory Board, and the fact he spoke German fluently. From an article in the 8/78 Binford’s Guide.