I remember the “mall” from my youth, but it barely registers that it ever actually had a name. The Red River Mall was a misguided attempt to revitalize Fargo’s downtown, which (whether directly or indirectly) led to downtown Fargo’s near-collapse in the late 80s and early 90s, and forcing the renewal plans that threaten to cause another Red River Mall-like slump.

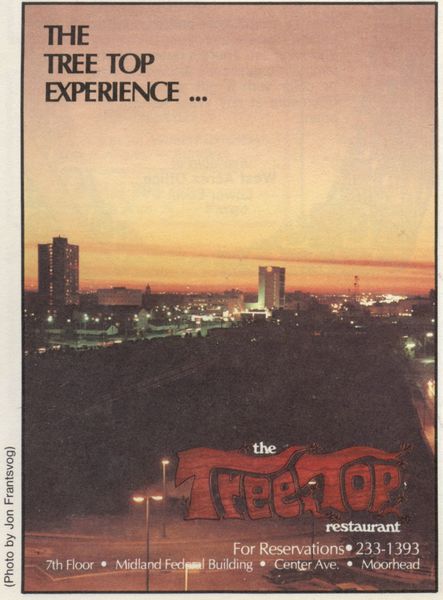

In the 1960s and early 1970s, the nationwide Urban Renewal movement hit Fargo and Moorhead: Moorhead got an actual indoor mall to replace the dozens of retail stores and apartments downtown. Fargo got tall buildings, open spaces, and the Red River Mall. The Mall wasn’t a direct knee-jerk reaction to the creation of the West Acres Mall, but it was hoped to counter the movement of stores away from the downtown area. Fargo’s retail center stretched from around 8th Avenue north to 5th Avenue South, and extended east to around 2nd Street and west to 10th Street. Modern Fargoans may be wrinkling their brows at this range, wondering how downtown Fargo was ever that big: today, Downtown starts at 6th Avenue and stops at Main, and barely extends a block off Broadway. The rest of those buildings? They were replaced by modern office buildings, they burned and were paved over instead of rebuilding, they were sacrificed in favor of flood protection, they were demolished to create parking lots, and they got absorbed by their neighbors.

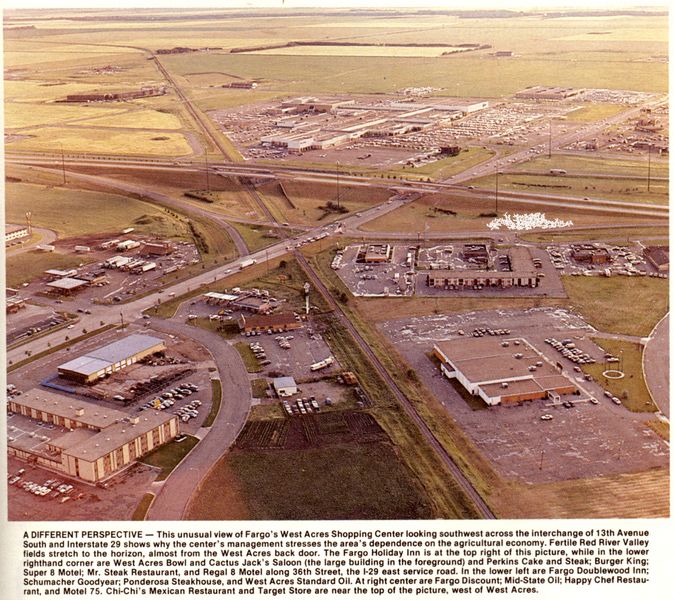

So, by the early 1970s, Downtown Fargo was in a poor position: it had a number of department stores, but its retail influence was shrinking. Small malls were popping up at the edges of town where new houses were being built. And then, West Acres gave the department stores the final boost to move out.

That left large, empty buildings, struggling locally-owned stores, and a loss of shoppers. The city, in its infinite wisdom, saw the possibility of turning Downtown Fargo into something akin to Nicollet Mall in Minneapolis.

Here’s how the plan went: Broadway, formerly two lanes with parking along all sides, would be turned into a winding, parking-less, snake-like street emulating the curvy nature of the Red River. Keeping to the curvy road, large cement pylons would mark the borders. To appeal to pedestrians, at their appropriate places along the “river”, marble place-markers represented the border cities. To keep rain and snow off pedestrians, overhanging roofs would line the street close to the buildings. Trees remained, or were planted for aesthetic reasons, with nice sitting places scattered throughout.

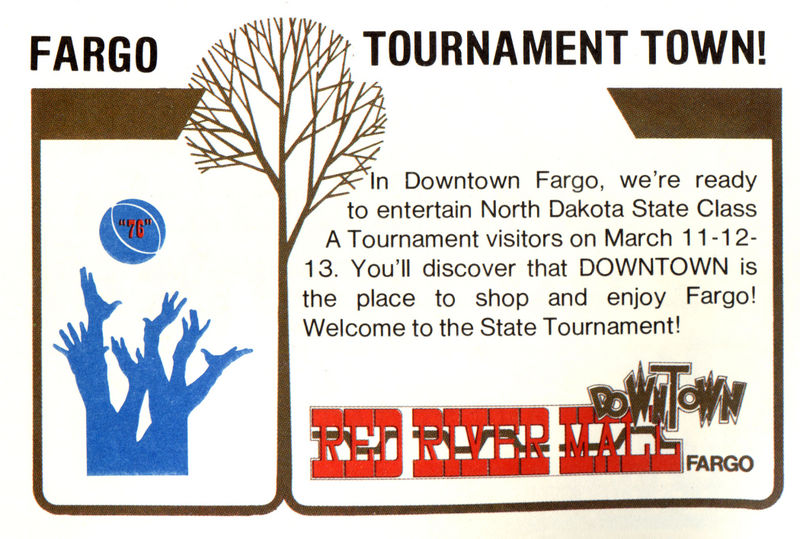

As you might guess, with the loss of large stores shoppers weren’t going downtown much, and now that Broadway was difficult to navigate they were less likely to do so. Sidewalk ceilings helped some, but weren’t enough encouragement. The Red River Mall eliminated a lot of downtown parking, which caused more buildings to disappear from along the streets, further reducing retail spaces in exchange for mostly-empty parking lots.

In 1976, optimism was still high: the Red River Mall was still an attraction. It was only a year or two after West Acres’ debut, so there was less evidence of replacement, as opposed to an expansion of retail opportunities. Downtown stores hoped that regional events like the basketball tournament would draw shoppers to our repackaged ‘shopping mall’ and stop by. Eventually, it became clear that the Red River Mall was nothing more than shiny wrapping paper on an unwanted, regifted chotchke: even its name slowly dropped out of popular use, and Broadway’s retail influence all but stopped.