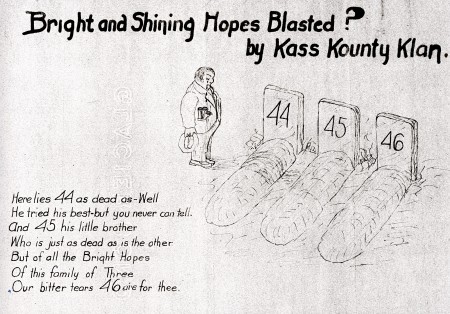

In the archives for State Senator William Martin — remember him? He suggested North Dakota secede from the US — is this unique image, so unique it bears a mention in the state archives indexes:

It’s titled “Bright and Shining Hopes Blasted? by the Kass Kounty Klan.”, and the poem reads:

It’s titled “Bright and Shining Hopes Blasted? by the Kass Kounty Klan.”, and the poem reads:

Here lies 44 as dead as Well

He tried his best-but you never can tell.

And 45 his little brother

Who is just as dead as the other

But of all the Bright Hopes

Of this family of Three

Our bitter tears 46 are for thee.

As you might guess from the group’s name, the Kass Kounty Klan was an ‘affiliate’ of the Ku Klux Klan, the US-born racist group that has been stubbornly causing trouble since the 19th century. The North Dakota arm of the group started in the mid-1920s, and quickly grew to a political influence in the region. By the 1930s, though, their power had faded and they remain a footnote of sad history in North Dakota.

Martin served in the state Congress in the late 1920s and early 1930s, so he came in towards the end of the Klan’s presence in North Dakota — at first, I assumed the image above was threatening in some way; combining the Klan with imagery of graves would seem to be a warning to their enemies.

By 1927 or so, the Kass Kounty Klan had lost steam: their northern counterparts in Grand Forks had gotten members elected to positions in government, but the Kass Kounty Klan never saw that level of support. In less than ten years, the group had disbanded, and I interpret the page above not as a threat, but as a requiem for the group late in its life. It could also be a satirical piece written by someone opposed to the Klan.

44, 45, and 46 are legislative district numbers in Cass County — they’ve moved around a bit over time, I couldn’t find a map for the 1920s, but those three districts have traditionally been Fargo state legislative districts. Happily, this comic shows the Klan’s political efforts as dead and buried. as it should be.