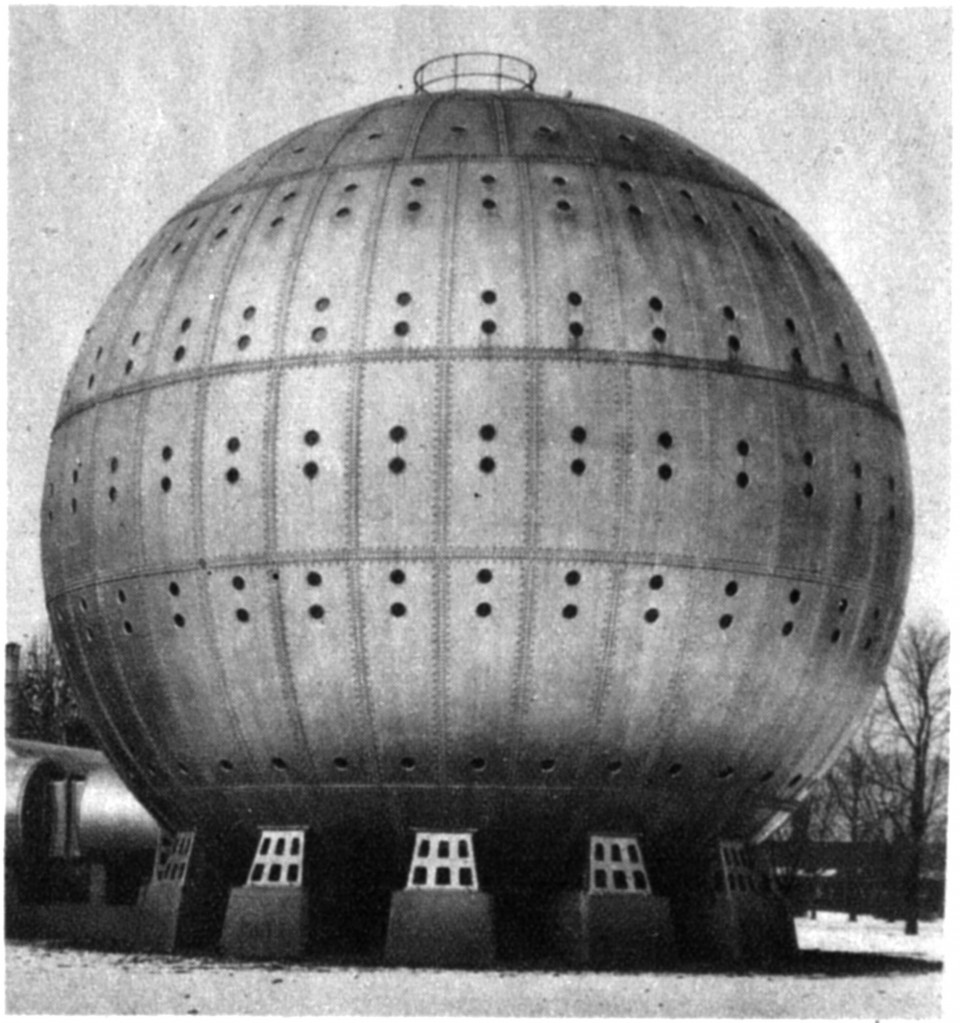

What is it — an oil tank? A spacecraft? A nuclear reactor? In 1928, this was the cutting-edge in medical technology: The Cunningham Sanitarium.

Dr. Orval J Cunningham was experimenting with the use of oxygen to treat a variety of diseases, particularly diabetes and asthma, at the University of Kansas in Kansas City, Missouri. Part of the process was to inhale oxygen through a glass tube for hours daily, and although Cunningham believed the treatment was successful, it was, well, boring to sit in one place for so long, just inhaling concentrated oxygen. He improved the technique by enclosing the patients in cylindrical tanks full of compressed oxygen, but those small enclosed spaces were still too inhibiting of daily life.

One of his patients, believed to be cured of diabetes by the oxygen treatments, was a friend of the King of Ball Bearings, Mr. Henry H Timken Jr. Timken, son of inventor Henry Timken Sr., the owner of Timken Roller Bearings Company, had both the money and the steel production capabilities to make Cunningham’s plans come to life. The building in the photo above was christened The Cunningham Sanitarium in 1928, and its spherical design was to allow the entire building to be pressurized above the normal air pressure, with a higher concentration of oxygen than normal air.

The building consisted of 38 bedrooms on three floors, with a recreation room on the top floor. An elevator ran through the center of the sphere. The walls were constructed of half-inch steel plates, and 350 portholes ringed the 64-foot-diameter ball. Patients would live in this concentrated, pressurized oxygen tent until cured, or so the theory goes.

The problem is, this wasn’t much of a cure. Cunningham’s theories were well-intentioned, but poorly tested. Few other doctors believed the treatment was viable, and now, ninety years later, the fact that modern hospitals aren’t giant metal balls lends to Cunningham’s unsuccessful methods. The ongoing Great Depression was no help to Cunningham’s giant ball, either: within five years, the Sanitarium was about to close its doors.

Another magnate of modern industry came to Cunningham’s aid. In 1934, James H. Rand III, son of James Rand Jr, proprietor of the Remington-Rand Company, showed interest in Cunningham’s work. While his father was revolutionizing the business electronics world, James The Third had left the family business to develop new inventions for the medical industry. At only 21 years old, Rand purchased the sphere and established The Ohio Institute of Oxygen Therapy.

Although Cunningham’s sphere may have given Rand a leg-up for his later inventions, which included an oxygen regulator and a variety of hospital fixtures, the Institute did not fare much better under Rand. 1937 was a particularly bad year for the spherical sanitarium. Dr. Cunningham passed away in February. In September the Institute for Oxygen Therapy was charged with violating Ohio securities laws, and a number of documents mysteriously disappeared from the state securities division offices. Shortly after, the sphere fell into disuse and was abandoned.

Around 1940 the building and land was purchased by the Cleveland Catholic Diocese to use as a youth center and summer camp. In November 1941, the Diocese was already considering ridding itself of the curiosity, but by 1942 the wartime scrap metal drives condemned the building to destruction. In March, 1942, the Cunningham Sanitarium was finally torn down on the orders of the U.S. War Production Board and the half-inch steel plate walls of the Cunningham Sanitarium, originally intended to cure disease, went into the production of tanks and warplanes.

Today, Cunningham’s theories haven’t been completely abandoned. High-pressure oxygen treatment still provides benefit in certain cases, even though it’s not anywhere near a cure for asthma or diabetes. The Catholic Diocese of Cleveland still owns the land that the Cunningham Sanitarium stood upon: it is now the location of Villa Angela-St. Joseph High School.